Payroll Taxes: Rates and Filing Deadlines

What Are Payroll Taxes?

Payroll taxes, sometimes called employment taxes, are any taxes that are withheld from or calculated as a percentage of an employee’s wages. This includes federal and state income tax withholding, social security and Medicare taxes, federal and state unemployment taxes, and state and local payroll taxes. Most payroll tax revenue is used to administer government benefit programs.

Small business owners are responsible for withholding, reporting, and paying payroll taxes. Whenever you pay your employees, there are certain taxes that you have to withhold from their paychecks. You also have to pay the employer’s share of payroll taxes. Add to this the responsibility of filing tax forms and making payroll tax deposits, and it’s no wonder that most small business owners feel intimidated.

Fortunately, small business taxes, including payroll taxes, aren’t as complicated as they seem. You just need to understand the different types of payroll taxes, who’s responsible for paying each, and the filing and payment deadlines. We’ll explain everything you need to know about payroll taxes and include the latest rates and filing deadlines.

Overview

Payroll taxes are the taxes used to fund programs like social security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance. Income tax withholding is also a type of payroll tax. Since the U.S. government is divided into federal, state, and local jurisdictions, there are federal, state, and local payroll taxes.

Here’s an overview of payroll taxes:

Federal Payroll Taxes

These are the three main federal payroll taxes:

- Federal income tax withholding

- When an employer pays an employee, the employer is responsible for withholding the proper amounts from the employee’s paycheck.

- The amounts withheld are determined by federal income tax tables, the rate of pay, and the exemptions claimed by the employee on the W-4 form.

- FICA taxes—Medicare and social security

- Employees and employers both pay FICA taxes, which fund the Medicare and social security programs.

- Employers should withhold FICA taxes from an employee’s paycheck and report withheld amounts to the IRS.

- Employers pay and report their own share of FICA taxes as well.

- FUTA taxes—Federal unemployment

- Employers contribute the entire amount due for FUTA taxes. FUTA taxes fund unemployment compensation benefits that people receive when they lose a job.

State and Local Payroll Taxes

Like the federal government, state and local governments also have payroll taxes, including state income taxes and state unemployment taxes (SUTA). Local taxes vary and can include anything from a flat income tax to a tiered transportation or school board tax.

These are the three main types of state and local payroll taxes:

- State income tax withholding

- Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Texas, Washington, and Wyoming are the only states without an income tax.

- Tennessee and New Hampshire only tax dividends and interest income, but not wages.

- In other states, employers are responsible for withholding state and local income taxes from an employee’s wages.

- SUTA taxes—State unemployment

- Employers must pay unemployment taxes at the state level as well. However, once an employer has a consistent record of on-time payments for SUTA taxes, they can claim a credit that reduces their FUTA taxes.

- Other state and local payroll taxes

- Additional payroll taxes vary by location. Taxes might include disability insurance payments, family leave payments, and more.

What Is the Payroll Tax Rate for 2020?

Ultimately, because payroll taxes consist of several individual taxes, there isn’t a single payroll tax rate. Therefore, as you’ll see in the chart below, we’ve broken out all of the payroll tax rates for 2020, along with who’s responsible for paying each tax and the wages to which the tax applies.

2020 Payroll Tax Rates

| Payroll Tax | Employee Pays | Employer Pays | Total | Applies To |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Federal income tax |

10% to 37%

|

None*

|

10% to 37%

|

All wages

|

|

State income tax |

0 to 13.3%

|

None*

|

0% to 13.3%

|

All wages

|

|

Social security tax |

6.2%

|

6.2%

|

12.4%

|

Wages up to $137,700

(Up from $132,900 in 2019) |

|

Medicare tax |

1.45%

|

1.45%

|

2.9%

|

All wages

|

|

Medicare surtax |

0.9%

|

None

|

0.9%

|

All wages paid in excess of $200,000

for single filers, $250,000 for joint filers |

|

Federal unemployment tax |

None

|

6%

|

6%

|

Wages up to $7,000

|

|

State unemployment tax |

Varies

|

Varies

|

1% to 3.7%

|

Varies

|

*Employers must separately pay business taxes and file a business tax return.

When calculating payroll taxes, you’ll want to keep in mind that all types of wages count. Salary, tips, bonuses, commissions, overtime pay, back pay, and accumulated sick pay are all considered taxable income. However, outside of regular wages, other types of wages are called supplemental wages.

The IRS offers employers a few different options for withholding taxes on supplemental wages. You can treat them as regular wages or separately withhold a flat tax from them. The flat tax rate is 37% if an employee receives supplemental wages in excess of $1 million per year. The rate falls to 22% for supplemental wages of $1 million or less.

How Do Payroll Taxes Work?

Now that we have a better sense of what payroll taxes are and what the different payroll tax rates look like for 2020, let’s break down how these taxes work in greater detail.

Income Taxes

Although income tax is a specific kind of tax on its own, it is usually categorized under payroll taxes due to the employer’s responsibility to withhold the proper amounts. These taxes are assessed on employee earnings, and typically go toward funding defense and national security programs. Employers are responsible for withholding taxes (in the form of a payroll deduction) based on the taxpayer’s W-4 withholding form. When the taxpayer files their income tax return, they will either pay any remaining balance or receive a tax refund.

Overall, the federal income tax system is a progressive tax system, where tax rates are higher for people with higher incomes.[1] Each taxpayer falls into a federal tax bracket. In 2020, there are seven tax brackets based on what you earn and your filing status—10%, 12%, 22%, 24%, 32%, 35%, and 37%. For example, a single filer who earns an annual salary of $60,000 will fall into the 22% tax bracket. For taxes due in April 2020, this individual must pay a flat $4,543, plus 22% on any amounts over $39,475.

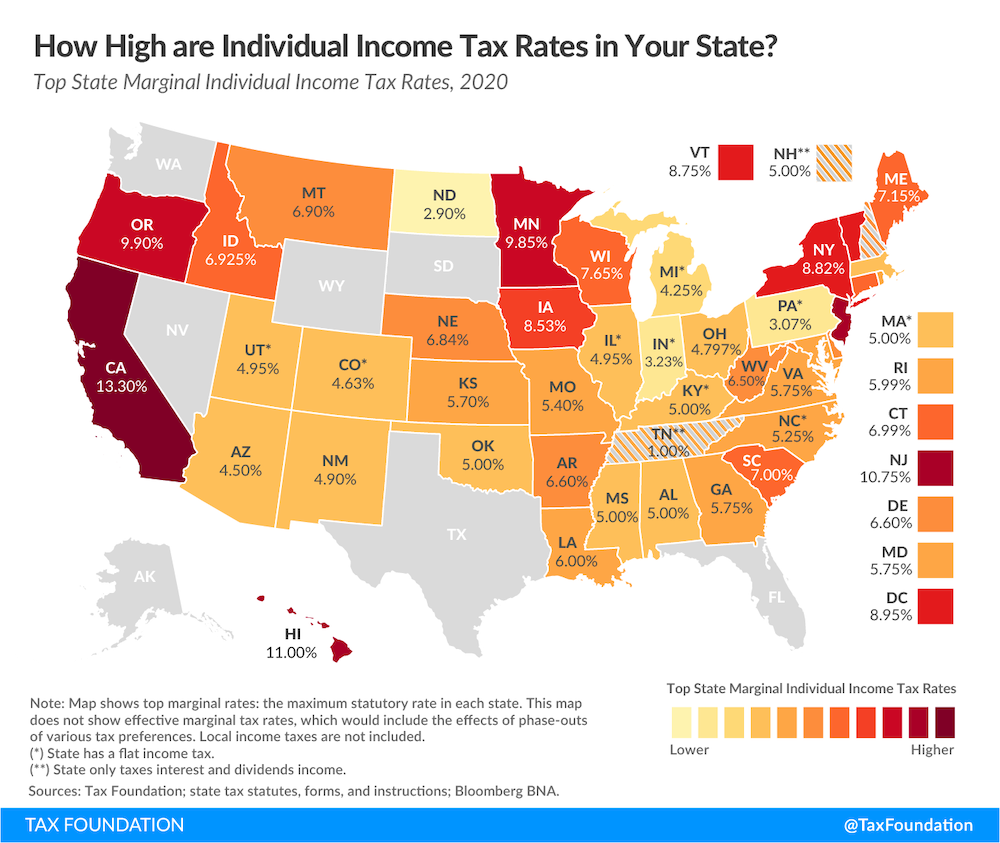

State income taxes vary considerably from state to state, but most states that have an income tax have a progressive income tax. Seven states don’t levy any income tax—Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Texas, Washington, and Wyoming. New Hampshire and Tennessee only charge income taxes on interest and dividend income, not on ordinary earnings from a job. As you can see in the graphic below, California levies the highest state income tax, 13.3% on employees with annual wages of $1 million or higher.

Image source: Tax Foundation

FICA Taxes

FICA stands for the Federal Insurance Contributions Act. FICA taxes are used to fund the nation’s social security and Medicare programs, and both employers and employees pay these taxes.

FICA taxes are actually made up of three different taxes:

- Social security tax – Employers and employees both pay 6.2% on wages up to $137,700. This means the maximum annual social security tax is $17,074.80, divided evenly between employer and employee.

- Medicare tax – Employers and employees both pay 1.45% in Medicare tax. There’s no wage cap, so the more an employee earns, the more the employee and the employer will pay in Medicare tax.

- Medicare surtax – Highly paid employees have to pay a 0.9% Medicare surtax. Employers must start withholding this tax from an employee’s paycheck as soon as their wages reach $200,000. Depending on an employee’s total combined income (with a spouse) and filing status, they might receive a refund for this tax. There is no employer share for the Medicare surtax.

Self-employed individuals pay the employer’s and employee’s share of social security and Medicare taxes—meaning 12.4% of business income for social security taxes and 2.9% of business income for Medicare. An owner of a sole proprietorship, a partner in a general partnership, a member of a limited liability company, and independent contractors and freelancers are considered self-employed and therefore have to pay these self-employment taxes.

FUTA and SUTA Taxes

FUTA stands for the Federal Unemployment Tax Act, and SUTA (State Unemployment Tax Act) is the state component. FUTA taxes are used to fund unemployment compensation programs. People receive unemployment compensation benefits when they lose their job.

Only employers pay FUTA and SUTA taxes. These are not taxes that you withhold from an employee’s paycheck. The federal FUTA tax is 6%, and the tax applies to the first $7,000 that you pay to an employee each year. This puts the maximum FUTA tax at $420 per employee each year.

As you might imagine, SUTA taxes vary considerably in each state, from as little in 1% in Iowa to as high as 3.689% in Pennsylvania. The federal government grants a credit of 5.4% for employers who pay their SUTA taxes in full and on time, bringing the effective FUTA tax rate down to 0.6%. The only exception is if your state is a credit reduction state. In 2019, only the U.S. Virgin Islands could be a credit reduction state. You have to pay SUTA taxes in any state where you have employees.

Self-employed individuals don’t pay FUTA or SUTA taxes, and therefore, they aren’t eligible to receive unemployment benefits.

Employer Payroll Tax Responsibilities

With all of this information in mind, you might be wondering what you have to do, as a small business owner, when it comes to payroll taxes. Essentially, as an employer, you’re held to certain government requirements.

Specifically, employer responsibilities for payroll taxes include the following:

- Report and pay the employer share of payroll taxes to proper federal, state, and local authorities.

- Calculate the employee share of payroll taxes and withhold these amounts from employees’ paychecks during every payroll in your schedule.

- File payroll tax returns in accordance with tax deadlines.

- Provide tax documentation to employees and independent contractors, such as the W-2 Form and 1099-MISC Form.

- Account for payroll expenses when you balance your books.

If you don’t want to handle these responsibilities on your own, payroll software or a professional employer organization can help you stay in compliance with federal, state, and local requirements. You might also choose to work with a business accountant or tax expert for advice on managing your payroll processes and filing your taxes correctly and on time.

As an employer, you’re responsible for completing, filing, and distributing W-2 forms for your employees at the conclusion of every year. Image source: IRS

Payroll Tax Deadlines and Forms for Employers

How do you fulfill your payroll tax responsibilities as a small business owner?

The IRS has a pay-you-go system for most payroll taxes, which means that you have to deposit your payroll taxes throughout the year. You also will need to report these taxes on the appropriate tax forms.

Here are the important deadlines and forms that you need to be aware of for each type of payroll tax. Note that if a filing deadline falls on a holiday or weekend, you have until the next business day to file.

FICA Tax and Income Tax Filing Requirements

You must fill out and file IRS Form 941 to report FICA tax and federal income tax that you’ve withheld from your employees’ wages. Form 941 is due quarterly on the last day of the month following the end of the quarter.

Here’s the schedule of due dates for filing Form 941:

- First quarter: Due April 30, for the period covering January 1 to March 31

- Second quarter: Due July 31, for the period covering April 1 to June 30

- Third quarter: Due October 31, for the period covering July 1 to September 30

- Fourth quarter: Due January 31, for the period covering October 1 to December 31

In most cases, you should not send any tax payment along with Form 941. You’ll need to separately deposit the FICA taxes and withheld income taxes that you report on Form 941. You can deposit these taxes on the Electronic Federal Tax Payment System (EFTPS). Tax deposits are due on either a semiweekly or monthly schedule depending on the amount of your payroll tax liability during a one-year lookback period (July 1 to June 30).

During that time period, if you reported taxes of $50,000 or less on Form 941, you’re a monthly depositor. In that case, taxes for payments made during a specific month are due by the 15th calendar day of the following month. If you reported taxes of more than $50,000 on Form 941 during the lookback period, you’re a semiweekly depositor. In that case, taxes for Wednesday, Thursday, or Friday paydays are due by the following Wednesday. Taxes for Monday, Tuesday, Saturday, or Sunday paydays are due by the following Friday.

IRS Form 941 is used to report FICA and federal income tax. Image source: IRS

FUTA and SUTA Tax Filing Requirements

In addition to completing IRS Form 941 for FICA and federal income tax, you’ll need to fill out and file IRS Form 940 to report FUTA taxes. The filing deadline for this form is January 31, extended to February 10 for business owners who deposited their FUTA taxes on time.

The quarterly deadlines for depositing your FUTA taxes are April 30, July 31, October 31, and January 31 (identical to the filing deadlines for Form 941). As with FICA taxes, you should deposit the FUTA taxes on EFTPS. If your FUTA tax liability is less than $500 in a year, however, you can include payment along with Form 940 instead of depositing the taxes on a quarterly basis.

At a state level, you must file quarterly wage detail reports to document SUTA amounts.

IRS Form 940 is used to report FUTA taxes. Image source: IRS

Employee Payroll Tax Responsibilities

Although, as a small business owner, you’ll mostly be responsible for the employer portion of payroll taxes, it’s important to understand what payroll tax responsibilities your employees have. Employee payroll tax responsibilities include the following:

- Provide correct withholding information on Form W-4.

- Update Form W-4 whenever there’s a change to the employee’s tax exemptions, like getting married or having a child.

- Regularly review paystubs, and ensure that the employer is making the right deductions.

- Let the employer know if you don’t receive a W-2 by early February.

- File taxes before April 15.

Ultimately, the exchange of accurate information should be a collaborative process between the employer and employee. It’s also a good idea to check in with your employees once or twice a year to ensure that all of their personal and tax information is up to date.

Payroll Taxes: Tips for Success

At the end of the day, with the sheer number of taxes, rules, and deadlines, payroll taxes can seem very intimidating. Luckily, however, in addition to getting a better understanding of how these taxes work, there are a handful of other actions you can take to ensure you’re meeting all of your responsibilities as an employer.

First, you can use payroll software to help you automate calculations, withholdings, deposits, and reporting. Next, you can work with a professional—either an accountant, tax expert, or HR consultant to evaluate your payroll compliance and ensure that you have everything set up correctly and are meeting all of your necessary deadlines. In particular, when it comes to filing and paying your taxes, investing in professional tax advice is always helpful—after all, if you file late or incorrectly, the IRS can charge penalties or fees.

Finally, you can implement a payroll process that extends throughout the year—so you know what to do when a new employee starts, when an employee needs to change their status, and when you need to pay your taxes. You’ll also want to make sure you are aware of any updates that are made to federal or state law regarding payroll taxes or the payroll tax rates. This way, you’ll be on top of all your payroll tax responsibilities—minimizing the possibility of errors or other issues that could negatively affect your business.

Article Sources:

- TaxPolicyCenter.org. “Are Federal Taxes Progressive?“

Priyanka Prakash, JD

Priyanka Prakash is a senior contributing writer at Fundera.

Priyanka specializes in small business finance, credit, law, and insurance, helping businesses owners navigate complicated concepts and decisions. Since earning her law degree from the University of Washington, Priyanka has spent half a decade writing on small business financial and legal concerns. Prior to joining Fundera, Priyanka was managing editor at a small business resource site and in-house counsel at a Y Combinator tech startup.

Related Posts

- How to Set Up Payroll for Your Small Business in 9 Steps

- The Small Business Health Options Program: What Businesses Need to Know

- 7 Benefits of Letting Employees Work Remotely

- 6 Ways to Help You Hire the Best Employees—and Prevent Turnover

- The 7 Different Personalities in the Workplace (And How to Manage Each of Them)