FUTA Tax Rate: What Business Owners Should Know About the Federal Unemployment Tax Act

This article has been reviewed by tax expert Erica Gellerman, CPA.

What Is the Federal Unemployment Tax Act?

The Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA) is a federal law that requires businesses to pay annually or quarterly to fund unemployment benefits for employees who lose their jobs. The FUTA tax rate is 6% of the first $7,000 of wages, though many businesses qualify for a tax credit that lowers it to 0.6%. Most businesses also have to comply with their state’s State Unemployment Tax Act (SUTA), which coordinates with the federal tax.

Small business owners have numerous tax obligations, and if your business has employees, your tax burden is even greater. As an employer, you’re responsible for both federal and state unemployment taxes. The Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA) is the federal law that requires business owners to pay taxes to fund unemployment compensation for employees who lose their jobs. The State Unemployment Tax Act (SUTA) serves the same purpose but in each state. This being said, most businesses with employees have to pay both FUTA and SUTA taxes.

If you’re a first-time business owner, you might be wondering exactly “what is a FUTA tax?” and “how does FUTA tax rate work?” as well as wondering what your responsibilities are to fulfill this obligation. Even if you’re an established business owner, you might still have questions regarding FUTA, like “What’s the FUTA tax rate for 2020?”

We’re here to help. In this guide, we’ll explain how the FUTA tax works, who has to pay it, what the FUTA tax rate is, and how and when to file your FUTA taxes. Plus, we’ll offer some top tips regarding this unemployment tax to help you avoid fines and keep your business taxes low.

How Does FUTA Work?

As mentioned above, the acronym FUTA refers to the Federal Unemployment Tax Act, which provides compensation for workers who are unemployed. If your business has employees, you’ll be responsible for FUTA taxes, as well as SUTA taxes, or state unemployment taxes.

The way the FUTA tax works is that you, as an employer, pay federal and state unemployment taxes which then fund unemployment insurance payments for employees who are laid off or lose their jobs through no fault of their own. Therefore, unlike the other payroll taxes—social security and Medicare, which are divided evenly between employers and employees—employees do not pay the FUTA payroll tax.

Whereas social security and Medicare taxes are withheld from employees’ paychecks, this is not the case with federal or state unemployment taxes. Instead, both the federal government and state governments collect unemployment taxes from employers and the federal government sends its portion to the states to supplement what the states collect.

Who Has to Pay FUTA and SUTA Taxes?

With this overview in mind, let’s dive into the details. As we mentioned, both FUTA and SUTA taxes are employer taxes, also often called payroll taxes. Therefore, if your business does not have any employees, you will not be responsible for federal or state unemployment taxes.

On the other hand, any business that falls into either of these criteria must pay FUTA taxes:

- You paid employees at least $1,500 in wages in a calendar quarter during the current or previous year

- You employed one or more workers for at least some part of the day during 20 or more different weeks in the current or previous year. This refers to full-time, part-time, and seasonal W-2 employees, but not independent contractors.

In general, you do not have to pay FUTA or SUTA taxes on your own income, unless your business is structured as a corporation. If you have a family-run corporation or partnership, your child’s wages (if 21 or older) and spouse’s wages do not count for FUTA and SUTA purposes. This being said, if your business has household or agricultural employees, the qualifications for whether you’re obligated to pay FUTA tax for these employees is slightly different. The IRS Employer’s Tax Guide can help you determine your FUTA tax responsibilities for these types of employees.

In terms of your SUTA requirements, these vary by state, so you’ll want to consult your state’s unemployment tax agency to determine if you have to pay SUTA taxes. Finally, certain types of businesses, such as nonprofits, religious institutions, and educational institutions, are exempt from paying FUTA and SUTA taxes.

FUTA Tax Rate for 2020

If you’re obligated to pay federal unemployment taxes as a business owner, the next thing you’ll likely want to know is how much you have to pay. Overall, both FUTA and SUTA tax rates are calculated based on the amount of an employee’s wages, up to a certain limit. These business tax rates and wage limits can change periodically.

Along these lines, Jennifer Affrunti, a CPA and controller at Nussbaum Berg Klein & Wolpow, PC, says:

“It is worth noting that the wage base and rates for FUTA have not increased… for quite a while. While there is nothing definitive right now, there are discussions in the works that would reinstate [higher taxes] sometime in the future.”

So, exactly how much are FUTA taxes?

The FUTA tax rate for 2019—which is expected to remain the same in 2020—is 6% on the first $7,000 in wages that you paid to an employee during the calendar year. After the first $7,000 in annual wages, you don’t have to pay federal unemployment taxes. Therefore, to calculate the FUTA tax for an employee who receives $6,000 in annual wages, you would simply multiply 6,000 by 0.06 to get $360. For an employee who receives more than the $7,000 in annual wages, you would perform the same calculation on the first $7,000—7,000 x 0.06— to get $420, the maximum you would pay in FUTA taxes for any single employee.

In this regard, it’s important to note that not all payments you make to employees are included in the annual wage that you use to calculate your FUTA payroll tax responsibility. Generally, gross wages, most fringe benefits, and certain employer contributions to employee retirement plans are included in this calculation and this total is subject to the 6% FUTA tax rate.

This being said, however, the federal government usually grants a business tax credit of 5.4% to business owners who have paid their state unemployment taxes on time—this effectively brings the FUTA tax rate down to 0.6%. Unfortunately, if your business is in a credit reduction state, you can’t claim the full 5.4% credit. Credit reduction states are states that have not repaid the federal government for money that they borrowed to fund unemployment insurance payments. The Department of Labor (DOL) maintains an updated list of credit reduction states.

In 2019, the Virgin Islands was the only credit reduction state. Employers paying Virgin Island SUTA taxes could receive a credit reduction of 2.7% in 2019, meaning that their final FUTA tax rate would come to 3.3% instead of 0.6%.

SUTA Tax Rate for 2020

Now that we’ve discussed the FUTA tax rate for 2019 and 2020 and how those calculations work, let’s break down SUTA taxes. As you may imagine, the SUTA tax rate will depend on the state and rates can range from as low as 0% to as high as 14.37%.[1] Similarly, wage bases also vary by state.

Many states charge lower rates for new businesses and higher rates for high-turnover industries like construction. Established businesses receive a rate based on experience. The “experience rating” and resulting SUTA rate will change based on the level of turnover and history of unemployment claims from your former employees.

This being said, once you apply for and receive your employer identification number (EIN), you can set up a SUTA tax account—called a state unemployment insurance (SUI) account in some states—with your state’s unemployment tax agency. The agency will notify you about your SUTA rate and wage base, and update you when these change.

SUTA Taxes for Businesses With Multiple Locations or Employees in Different States

If your business has locations in different states or employees who work in one state and live in another (or even remote employees), you can use the U.S. Department of Labor’s five-part test for multi-state employees to determine which state you must remit your tax to. You must consider each of the following:

- Localization of services (where the employee works most of the time)

- The employee’s base of operations

- Place of management, direction, and control

- The employee’s residence

- Whether the states in question have reciprocal agreements

In practice, the test usually means that you have to pay unemployment taxes in the state where the employee works and performs services most of the time. Some states have reciprocal agreements with nearby states, allowing employers allowing employers to choose the state of coverage.

When and How to File and Pay FUTA Taxes

So, now that we know who has to pay unemployment taxes and what the FUTA tax rate looks like, let’s talk about how your business will fulfill these tax obligations.

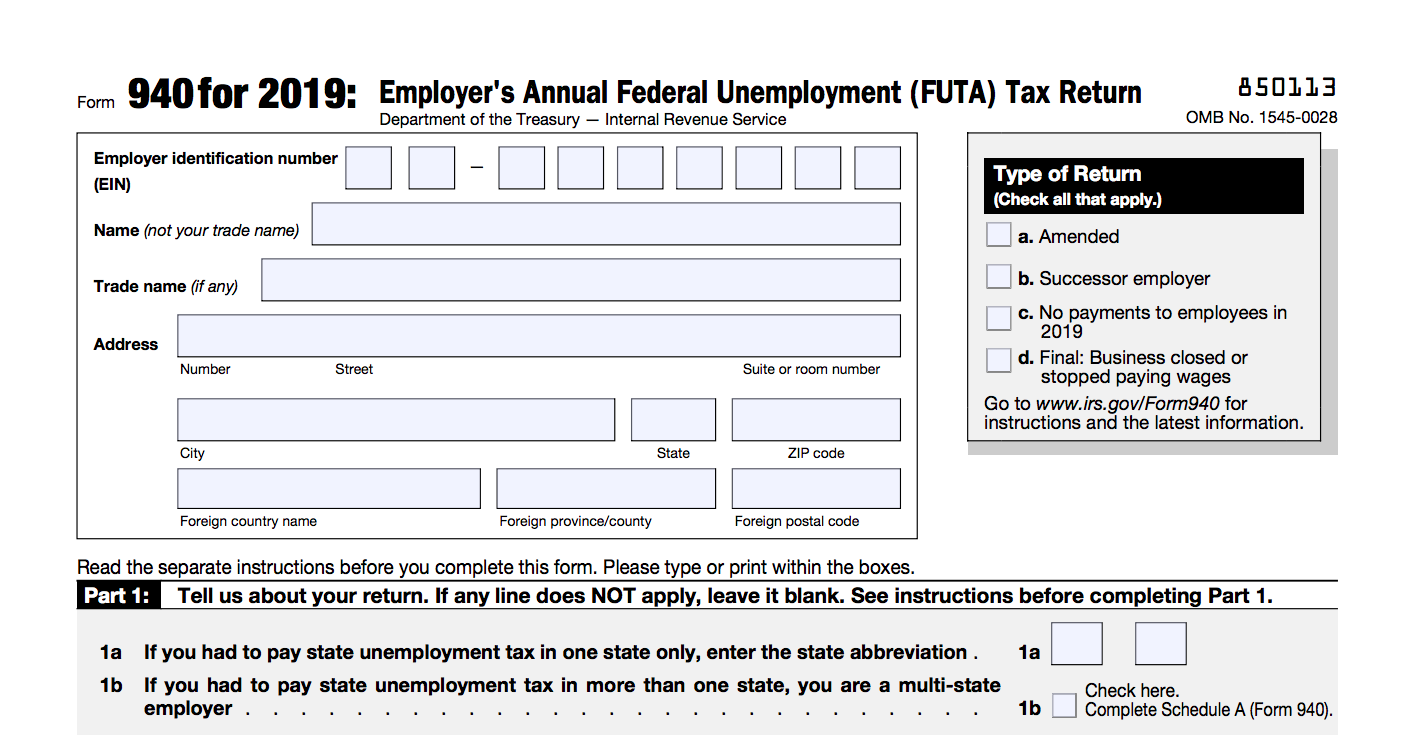

First, the form used to report FUTA taxes is IRS Form 940 pictured, in part, above. This form must be filed with the IRS by January 31 of each year (or the next business day if this falls on a weekend). The catch with FUTA taxes, however, is that the due date for filing Form 940 and the due date for actually paying the taxes are different. If you pay your taxes on time, the deadline for filing Form 940 gets extended to the second Monday in February. Here’s a video overview on how to fill out Form 940, including an example:

With FUTA taxes, therefore, it’s very likely you’ll be required to pay on a quarterly basis even though you only need to complete Form 940 once a year.

According to Affrunti, a common mistake is thinking that “FUTA requires an annual filing. Employers sometimes mistake their payment liability and may assume the payment is always due with the filing. Once an employer’s liability reaches $500, however, they are required to submit the tax on a quarterly basis. If you do not pay it in time, you could incur penalties.”

This being said, if you expect your total FUTA payroll tax liability to be greater than $500 for the year, you must deposit your taxes on a quarterly basis. If your FUTA tax liability for the quarter is lower than $500, then roll over that amount to the next quarter. Once your total FUTA tax liability in a quarter (including rolled over amounts) reaches $500, then you should deposit your payment no later than the last day of the following quarter. If the due date for making your deposit falls on a weekend day or on a federal holiday you’ll have to make the deposit by the following business day.

The quarterly due dates for depositing FUTA taxes, then, are as follows:

- First-quarter (January 1 to March 31): Payment due by April 30

- Second-quarter (April 1 to June 30): Payment due by July 31

- Third-quarter (July 1 to September 30): Payment due by October 31

- Fourth-quarter (October 1 to December 31): Payment due by January 30

Your FUTA tax payments should be made using the electronic federal tax payment system (EFTPS).

If your total FUTA tax liability is under $500 for the year, you don’t have to deposit your FUTA taxes quarterly. You can either choose to be a quarterly depositor or to pay your taxes once per year when you file Form 940. With all of this in mind, it’s important to remember that SUTA tax filing deadlines might differ from the federal deadlines, so again, you’ll want to contact your state unemployment agency to learn the details for your business.

Tips for Managing Your Business’s FUTA and SUTA Taxes

Ultimately, if you’re an employer, paying FUTA and SUTA taxes is unavoidable. The good news, however, is that the tax burden for these taxes is usually relatively low compared to other payroll taxes (like FICA taxes) and income taxes.

Therefore, to help you manage these taxes and ensure that you’re keeping your FUTA and SUTA taxes as low as possible, you can follow these four best practices:

File on Time

This may seem obvious, but with the other tax and general business responsibilities you have, it can be easy for a deadline to sneak up on you. This being said, whether you pay FUTA or SUTA taxes annually or quarterly, it’s important to pay on time. If you fail to pay on time, the IRS and your state unemployment agency will charge fees. In fact, the IRS penalties for late payment of employment taxes range from 2% to 25%, depending on how late you are.[2] These are completely avoidable fees as long as you stick to deadlines.

Plus, by adhering to deadlines and not waiting until the last minute, you’ll be less likely to make errors in your deposits or filing of Form 940, which will save you the time, effort, and money, for having to amend any mistakes.

Keep Turnover Low

One thing to keep in mind is that both FUTA and SUTA taxes are calculated from a wage base. The FUTA wage base, as we’ve discussed, is $7,000. This means you only have to pay FUTA taxes on the first $7,000 of an employee’s annual wages—which also means that every time you hire a new employee, the FUTA wage base kicks in anew.

This being said, say, for example, you have a customer service associate who’s paid $40,000 per year. If the same person has occupied that role for the last year, you’ve only paid $42 in federal unemployment taxes for that employee, (if you qualify for the maximum tax credit) plus additional state taxes. On the other hand, if you’ve hired four different people for that role in the last year, then you’ve quadrupled your FUTA tax burden to $168.

Therefore, the key here is to be a great employer and keep your employee turnover as low as possible. If your budget is tight, you can try to avoid layoffs by increasing cross-departmental transfers. These types of strategies will keep your FUTA and SUTA taxes low.

Respond to Unemployment Claims

As we mentioned earlier, your SUTA tax rate is based on your company’s employment history. Companies with high levels of turnover and large numbers of unemployment claims have to pay higher SUTA taxes. To keep rates down, you’ll want to respond to unemployment claims as soon as they’re filed.

Most claims for unemployment insurance are legitimate, but you should always respond if there appear to be any questionable claims. Most states give employers the opportunity to appeal a claim for unemployment compensation. If anything appears fishy (e.g. the employee provides the wrong termination date or states the wrong salary), you should respond as soon as possible. Blocking fraudulent unemployment claims will also keep your SUTA rates low.

Use a Payroll Service or PEO

Paying FUTA and SUTA taxes is pretty straightforward, at least if all your employees live in the state where your business is located. The process gets a little trickier when you have a business with multiple locations, remote employees, or employees who work in one state while living in another.

In those cases, using a small business payroll service or a professional employer organization (PEO) can help simplify things and take on these responsibilities for your business. To explain, a payroll provider or PEO will automate your employment taxes—with a few clicks and some information about your workforce, they’ll make sure to file the right forms on your behalf and send the right payments.

This being said, PEOs go an additional step further. PEOs pool together many small businesses and act as a co-employer to everyone who works in those businesses. Some states use the experience rating of the PEO, rather than the actual business, to calculate SUTA rates. This can be very helpful to a business that has experienced a lot of turnover. In this way, you essentially get to piggyback off the larger size and lower turnover rate of the professional employer organization, resulting in lower SUTA rates.

The Bottom Line

At the end of the day, although business taxes can be complex and difficult, FUTA and SUTA taxes are relatively inexpensive and simple compared to other taxes. Plus, not only are the rules for paying FUTA taxes pretty straightforward, but the federal government (and most states) allow for online payments—which makes the process all the more quick and affordable for your business.

Moreover, the FUTA tax rate is standard for most businesses—0.6% on the first $7,000 in annual wages (if you qualify for the maximum tax credit). With this in mind, although your SUTA taxes will be much more variable, this also means you have more control over your rate. By filing on time and maintaining a work environment where your employees want to stay, you can keep your SUTA tax rates low.

This being said, you’ll also want to remember that different resources, including payroll services, PEO, accountants, and business tax advisors, can be invaluable resources. When in doubt, you’ll want to consult a professional who can answer your questions and help ensure that your tax obligations are met wholly, accurately, and efficiently.

Article Sources:

- DWD.Wisconsin.gov. “Unemployment Insurance 2020 Tax Rate“

- SmallBusiness.FindLaw.com. “Penalties for Violating Federal Employment Tax Laws“

Priyanka Prakash, JD

Priyanka Prakash is a senior contributing writer at Fundera.

Priyanka specializes in small business finance, credit, law, and insurance, helping businesses owners navigate complicated concepts and decisions. Since earning her law degree from the University of Washington, Priyanka has spent half a decade writing on small business financial and legal concerns. Prior to joining Fundera, Priyanka was managing editor at a small business resource site and in-house counsel at a Y Combinator tech startup.

Featured

QuickBooks Online

Smarter features made for your business. Buy today and save 50% off for the first 3 months.